Laguna’s 36-Foot Height Limit

From the Village Laguna Newsletter, 2011, marking the 40th anniversary of the height initiative

August 3 is the fortieth anniversary of the initiative that established Laguna’s 36-foot height limit, and Village Laguna, whose founding members created the initiative, is celebrating at our annual picnic on August 29 (see back page) and, jointly with the Laguna Canyon Conservancy, on September 12 (call Ed Drollinger, 494-6465, to reserve a place for dinner [$10 for LCC members, $20 for others] at Tivoli Terrace).

In the year it all happened, 1971, the city was just getting started on curbside recycling. South Coast Community Hospital was preparing for expansion. Aliso Pier and Salt Creek Beach opened to the public. Eiler Larsen had a birthday party in Bluebird Park. A pound of ground beef cost 58 cents and you could buy a three-bedroom, two-bath house with an ocean view for $46,500.

The city was developing a General Plan, and a 25-member citizens’ advisory committee had recommended that one of its goals be to “maintain a village atmosphere and a sense of relaxation, peace, and tranquility.”

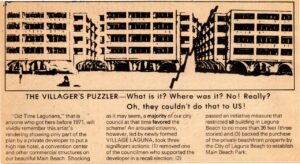

At the same time, a study commissioned by the City Council had recommended a doubling of the city’s hotel rooms to increase tourism revenue. A hotel-motel zone was proposed for a number of beachfront properties that were zoned both residential and commercial and therefore considered “unsuitable for the development the city needs”—from Laguna Avenue to Legion, from St. Ann’s to Thalia, and from Mountain to Agate.

Maximum building heights in the city’s two commercial zones were 30 and 50 feet at the time. The Surf and Sand Hotel had recently been granted a variance to build to 58 feet, and a 95-foot hotel at the north end of Main Beach was believed to be on the drawing board. In the Planning Commission’s hearings on the proposal in January, a maximum height of 70 feet was being considered. One of those hearings drew some 250 people, all but a few opposed to the idea.

As Phyllis Sweeney (a founding member of Village Laguna and later mayor) later wrote, “The citizens were outraged. Residents stormed the Planning Commission meetings. At one meeting, Judy Ronaky, the Commission clerk, read 47 letters in opposition. The commissioners’ response was that the objections were from only a small vocal minority. No one would listen. People were meeting in each other’s homes. Arnold [Hano], Fran [Englehardt], Joyce Dusenberry, and others formed a committee.” (Other members of this early group, already calling itself Village Laguna, were Roger McErlane, Bill Leak, Thomasina Gunn, Joe Tomchak, Nate Rynn, Mildred Hannum, and Corky Smith.) Eventually the Planning Commission settled on a 50-foot maximum height, and before the recommendation could reach the City Council a citizens’ group of five filed a notice of intention to circulate petitions for an initiative that would modify the building code to limit buildings to 36 feet above the highest point of grade citywide. Attorney Ralph Benson, engineer Merritt Trease, environmental biologist Philip Rundel, Arnold Hano, and Marjory Adams Darling signed the notice, which appeared in the Laguna News-Post on February 13. Then, when the required waiting period was over, volunteers, led by Phyllis Sweeney, began collecting signatures.

Phyllis continues: “Petition tables were set up at Boat Canyon Safeway, Acord’s Market, Albertson’s, Gene’s Market, and the Alpha Beta. Volunteers manned the tables every day, all day. We had our attorney activists available to explain right-to-petition laws to hostile store managers, who threatened to call the police. The people, however, stood in line to sign. People brought aged mothers who could barely write to sign. People from Emerald Bay were chagrined to learn that they couldn’t sign. Everyone wanted to.”

“The plan was to launch the drive on Tuesday night [March 9] at the Woman’s Club. It was decided to get a head start by collecting signatures over the weekend, thus inspiring the volunteers Tuesday evening. Each volunteer was asked to phone at the end of each shift the number of signatures obtained. It was like election central Saturday and Sunday at my house as the numbers were phoned in! When the totals from the trial run totaled just 30 signatures short of what was needed to qualify, and we hadn’t even started yet, my call to Arnold verged on speechless hysteria!”

The goal was 1,140 signatures, 15% of the city’s registered voters, and in the end 3,049 signatures were certified as valid. Faced with these figures at its May 19 meeting, the City Council called a special election to decide the issue on August 3.

Opponents of the height limit (the newspaper, the Board of Realtors) argued variously that sound planning would require waiting until the General Plan was completed to consider any changes; that a limit wasn’t really necessary because the cost of high-rise construction would be a strong deterrent; that “the woods were not exactly full of developers eager to build on our oceanfront”; that there weren’t any views to be had from the areas in question anyway; that the hospital and many of Laguna’s outstanding churches couldn’t have been built under a 36-foot limit; that if buildings were limited in height they would have to be wider; that a height limit would restrain “the very forces which have made the city singular and attractive”; and that what Laguna needed was a return to the rule of law and reason (“To hell with the tactics of revolution sweeping our community and our nation!”).

In the last weeks before the election, a local realtor went to court to try to stop it, arguing that you can’t change zoning by initiative, and the judge agreed. Attorney Bill Wilcoxen appealed, and the ruling was overturned, allowing the election to proceed.

On August 3, 62 percent (4,920) of Laguna’s registered voters turned out (a record, according to the City Clerk), and 75 percent of them voted yes.